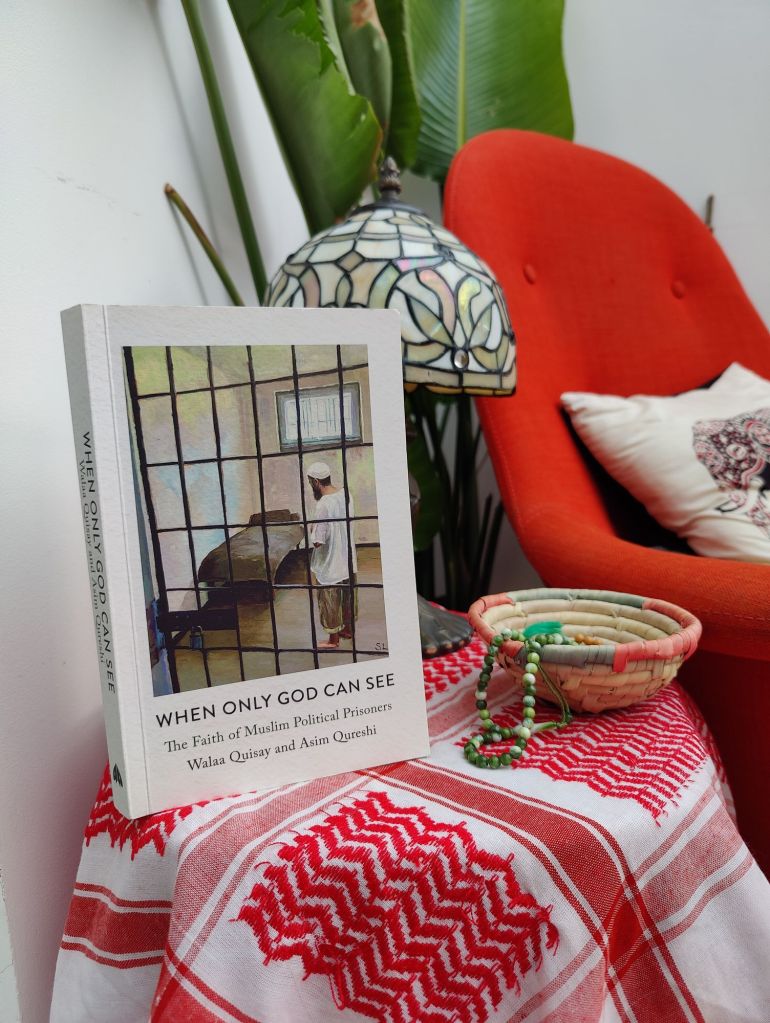

I read Malcolm X’s autobiography in January this year and it profoundly shifted something within me. A considerable part of the book is set during Malcolm’s years in Prison and it testifies to all the learning, reading and growing-up he did during his incarceration, particularly how he found God in the unlikeliest of places. It was also the first time I read about someone’s experience of the penal system in such detail and I was left intrigued. I’ve always been a prison abolitionist, and have read multiple texts on the prison system, the industrial complex and super prisons of the modern era, and the racism and colonial legacy these systems were built on and continue to maintain. However, I’ve never read anything specifically and solely about the experience of political prisoners especially in relation to their faith. When Only God Can See is the experience of Muslim prisoners during the “war on terror” commencing from September 2001, although the authors acknowledge that the subversion of legal norms and criminalising of communities and identities was in process long before that eventful September.

I bought this book during a Pluto Press sale, and in truth it wasn’t one that I planned on reading. I liked the concept, but the content felt intimidating. Potentially too intellectual for me, and therefore a struggle to read, but it also felt quite abstract and distant, something I might struggle to relate to. These were men and women who were deemed “terrorists” by the state and had disappeared into a complex systems of prisons, known and unknown, across the world. The book focuses mostly on the United States and Egyptian prisons (including sites where prisoners could be ‘disappeared’ such as black sites, rendition, proxy detention, military detention facilities and civilian buildings) but acknowledges the complicity of other nations in these arrests. “For example, 85 per cent of those detained in Guantanamo, were individuals sold to the US by the Pakistani government for $5,000 each. Many were aid workers, business people or ordinary civilians”. Arrestees would then be sent to sites across the Middle East where they would be subjected to torture in cooperation with the United States. This would allow for both forced confessions but also permit the US to escape legal or moral culpability.

The book is divided into seven chapters starting with Custody and ending with Faith and Resistance. In between there are discussions on Prayers, Ummah (community), Belief, Crisis and the Quran, Ethereal Beliefs and Torture. The penultimate chapter on torture is particularly difficult to read as it discusses cultural and sexual humiliation of prisoners including sexual violence against pregnant women, but it is also one of the most important sections of the book.

When Only God Can See isn’t simply a list of all the horrors prisoners face during their (often illegal) detentions. Surprisingly it is an uplifting and hopeful read. The section on Ummah describes how the prisoners would rally together to support, learn, teach, and comfort each other. How congregational prayers (although often restricted or completely barred) created community. Other chapters detail how reciting the Quran comforted detainees in their darkest hours. One prisoner, originally from Karachi, speaks about how he wasn’t religious before his abduction but during his incarceration he memorised the whole Quran, with the help of fellow prisoners correcting his recitation through drainpipe conversations.

One of the most devastating observations within this book is how complicit other “Muslims” were in the arresting, torturing and subsequent handing over of prisoners. In some instances, officers would ask the detainees to forgive them, they are just following orders, whilst others would beg those now in chains and with hoods over their heads to not make dua against them. Others would deny them the right to pray and in one absolutely jaw dropping confession, a senior prison officer appears to mock Allah (SWT) by stating “Around here I say be, and it is”. The cognitive dissonance of knowing these powerful verses from the Quran and then using them to oppress others and somehow believing they would avoid punishment.

There are so many parables from the Quran that are relived through the lives of these men and women. What was really powerful to me as a Muslim reader was learning how they applied the verse of the Quran to their own personal situations and how they found comfort in those words. Many spoke about Surah Yusuf, and his (AS) unjust imprisonment as well as the strength they got from the stories of Prophet Musa (AS). The prisoners’ reflections were particularly poignant, especially during their most difficult trials. One Prisoners speaks of being on the cusp of losing his faith until he stumbles across the verses in Surah Mariyam where she cries “I wish I had died before this and became long forgotten and non existent.” (19:23). Reading this verse reminded him that Allah (SWT) provides for His servants in the most miraculous of ways and that his Lord had not forsaken him. Another prisoner in Egypt contemplates that prisons are bought up twice in the Quran and both times in Egypt and in relation to unjust rulers.

I’m not very well versed in dreams, jinn and other ethereal beings. Whilst I fully believe in them, as they are mentioned in the Quran and sunnah, and I do my morning and evening adhkar (prayers) for protection I haven’t ever really delved into that world in my own learning. I’m not surprised however that these beliefs play a major role in the lives of some prisoners. Dreams in particular played an important role in maintaining hope for some. One of the brothers in Guantanamo Bay makes a really heart warming observation: “The Jinn were there initially, but they eventually left, as nearly 24 hours a day the Quran was being recited at Guantanamo Bay – the brothers were buzzing like bees with their recitation” Even though these men were imprisoned, tortured, sexually abused and experienced the worst of human behaviours, they held on tight to the rope of Allah, especially the Quran, and it is truly humbling to learn about their efforts.

In the United States prisoners spoke candidly about the dehumanisation and abuse they faced from the guards. From strip searches, cameras in toilets and showers and female guards leering and laughing at them as they were made to pose in humiliating and compromising positions. The restriction of water and not being permitted to make wudu (ritual cleansing), not knowing what time of day it was for prayers, insufficient food for Ramadan, the list goes on and on. It was even impermissible for Muslim men to wear their trousers above their ankles until 2015, when one of the prisoners bought a legal challenge and won. All these policies were to inhibit worship and specifically targeted Muslims. One prisoner speaks about reading Sylvaine Diouf book, Servants of Allah which documents the experience of Black Muslims during the transatlantic slave trade and being able to relate to that experience over any of the others he had read from Islamic history. Whilst acknowledging they suffered a great deal more, he also highlights the evil within the psyche of a people willing to treat other human beings in this way, and also of those, like the vast majority of us, who are happy to look away.

When Only God Can See allowed me to look into the reality of prisoner life, with firsthand accounts of their experiences. What really struck me was how resilient and resourceful many of these people were, even in these toughest of conditions. I have never considered how much preparing goes into a hunger strike for example. Not only for one’s own body but also looking into the Islamic framework for justification. Nothing these prisoners did was without deep contemplation and consideration of their faith. These brothers and sisters, many of whom found their faith in prison, were truly inspiring to me. I couldn’t help but think of my own rushed prayers and how I take free flowing water for granted. Theirs is not just a struggle for freedom but it felt like a fight for our faith.

At a time where more and more people are being arrested for their political beliefs, many of whom are Muslims, this book is an important illustration of what life behind bars entails. The level of psychological warfare these people have to navigate, even before being charged with any offense is bewildering. Using a prisoner’s faith as a weapon against them and the degrading, humiliating and often illegal methods that are employed to get confessions is astounding. How are we allowing these prisons and these systems to operate in spaces we call humane. How can we raise children in a world that treats humans in ways that most of us would never even think to treat an animal?

When Only God Can See highlights the failure of journalism. If I hadn’t already lost faith in heritage media, this book and what it uncovers about the treatment of prisoners, who irrespective of guilt, are still people, would have been the final straw. The slippery slope into authoritarianism is well under way, and the fact that our media haven’t been holding power to account is very disturbing. Journalism was once about keeping the public informed, and now it seems to only tow the establishments line. All the while people are being snatched off our streets and sent to secret detention centres across the globe, tortured into giving false confessions and then sent back to their host country to languish in solitary confinement for decades, without ever knowing the crimes for which they were initially abducted. And no one is safe. You might think it could never happen to you, but then so did the prisoners in this book, who were simply travelling from the UK or to the US. In one instance a woman was snatched off the streets because it was assumed she was protesting. Isn’t this our reality in the UK where every week innocent people are jailed for their political views? Can we please stop pretending that any of us are safe, if some of us are not.