For the most part I thought this was a really insightful introduction to the life of Frantz Fanon. It chronicles his birth in Martinique, a French Colony, where although slavery had been abolished, the vast majority of the population, which was black, continued to live and work in subordinate positions. At the age of 10, fanon recognised that the history they were being taught was based on denial, “that the order of things we were being presented with was a falsehood”. This realisation happened during a school trip when he visited a monument of Victor Schoelcher, a white abolitionist who abolished slavery in the French colonies. Fanon wondered why he was being honoured whilst the slaves he “freed” were not. As a young man he took part in the Second World War, and later moves to France to Study Medicine, which he subsequently changed to Psychiatry. In the early 1950s Fanon moved to Algeria where the most radical and revolutionary elements of his story, his politics and philosophy emerged.

At 17 Fanon fought alongside the “Free” French Army against the Nazis in Morocco, where he was shocked to witness the racial hierarchy in the French Army. It was the Arabs at the bottom, despised and discriminated against, then the African troops, mainly from Senegal, and then the West Indians. It was always the white officers in command. When he moved on to Algeria he was further disturbed at the depth of hatred the French had towards the Muslims and the Jews.

After the war Fanon returned to Martinique where he was involved in local politics and became increasingly close to Aimé Césaire, a Martiniquais poet, author, and Politian. He was one of the founders of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature, and had a great influence on young Fanon’s thinking. Fanon took part in the campaign to help him get elected to the French Parliament as a member of the Communist party, although Fanon was never a member of the party himself. By 1947 Fanon had left Martinique for Lyon in France to pursue a career in medicine.

Fanon continued being political during university and participated in anti colonialism demonstrations, engaged in debates and even wrote for a literary journal, addressed to students in the French colonies. Fanon became increasingly interested in the relationship between the social and psychological components of racism, and through his study of Marxism he was convinced that racism is intricately tied with economic conditions. Therefore, in the fourth year of medical school, he decided to forgo a residency in medicine and instead become a psychiatrist. For his thesis he submitted an initial version of Black Skin, White Mask, however his professor, Jean Dechaume, rejected it for being permeated by “the authors subjectivity”. He managed to hand in and successfully defend another thesis and Black Skin, White Mask was published in 1952.

Once Fanon qualified he did a brief stint in Martinique but soon returned to France. Then in 1953 he moved to Algeria, which would prove to be the major turning point in his life. Algeria was also a French Colony with the minority Europeans monopolising economic and political power. In Algeria Fanon gathered new insights on mental health, as well as Muslims and Algerian culture, which went on to influence his subsequent works.

The book goes into a lot of details on which philosophers and philosophy’s Fanon engaged with and which he deeply disagreed with. What is really striking though is how his practice of psychiatry led him to his revolutionary politics, and how it in turn impacted his work as a psychiatrist. His involvement in the Algerian Liberation Movement (FLN) in which he considered joining the guerrillas, although he never did, is a turning point in his own philosophies and ideologies around emancipation.

The Hungarian revolution and the Franco-British-Israeli invasion of the Suez were two events that highlighted to Fanon the desperate and inconsistent state of European politics. The attempt to invade Suez was an example of the French trying desperately to maintain their control over Algeria, and the lengths they were willing to go to. The Hungarian revolution highlighted the obvious racism in France and Western Europe. Whilst hardly anyone in the French Left had flinched at the butchering of Algerians, tens of thousands of communists, in France and Western Europe, now tore up their party cards and left the Communist Party in response to the brutal Soviet repression of the workers revolution in Budapest. This was the beginning of the end of Fanon’s relationship with France.

Fanon became deeply involved with the Algerian Liberation movement, even becoming close to some of its senior players. He was expelled from Algeria in 1957 and moved to neighbouring Tunisia, which had become independent in 1956, from where he continued his revolutionary politics. He was a journalist for the FLN’s publication, El Moudjahid, which came out in both Arabic and French editions. Fanon wrote for the French edition and was massively critical of the French Political Left. Figures such as Foucault remained silent on the issue of Algeria throughout the 1950’s and early 60’s, even though Algeria was THE defining issue in French society at the time. To this day, writes Hudis, many in French society, including those on the left, deny the critical importance of race in shaping social relations. These blindspots have often stopped them from acknowledging the terror that France imposed on Algerian society from 1954 to 1962, which is considered amongst the gravest crimes against humanity of the twentieth century.

Fanon’s writes some really interesting things in A Dying Colonialism. He acknowledges that the FLN prohibited the use of torture against captured soldiers, as well as indiscriminate attacks against civilians. Recognising the brutality and violent repression of the French does not justify replicating their methods. As a Muslim reader, and one cannot forget that Algeria is a Muslim country, these words very much echo the sentiments of the great Libyan anti-colonial liberation fighter, Omar Mukhtar, who protected two surviving Italian prisoners, saying ‘We do not kill prisoners,’ when a fellow warrior said ‘They do it to us’, Omar Mukhtar responded with the words: ‘They are not our teachers’. To a reader familiar with Islamic ideology, Fanon’s shift in thinking is very much in line with many Islamic principles.

It is therefore quite surprising the lengths the author goes to, to disassociate Fanon from the impact Islam may have had on his writing. A Dying Colonialism starts with the chapter Algeria Unveiled, in which Fanon discusses how the wearing of the veil, (hijab) is part of how Muslim women in Algeria resisted the modernising tendencies of the colonial power. Fanon wrote “the veil was worn because tradition demanded a rigid separation of the sexes, but also because the occupier was bent on unveiling Algeria” He went on to say “this woman who sees without being seen frustrates the coloniser. There is no reciprocity… He does not see her”. Hudis concludes that Fanon does not endorse the veil, and makes an arbitrary link with another passage from the book linking the anti-colonial struggle in Algerian society to “turning back, a regression” to their previous traditions. It’s evident that Algerian’s turned back to the traditions of Islam, they rejected the “modernization” and colonialism of their occupiers and preferred their own culture, traditions, society and religion to that of Western Europe. Why is Islam, and it’s values and traditions, regression in Hudis’s opinion? The French have always been obsessed with Muslims women’s bodies, it appears the author is also allowing his own orientalist voice to merge with Fanon’s.

Fanon goes to great lengths to understand Islam and Algerian Muslim society. He learned about islamic religious and cultural practices, both as a psychiatrist and a revolutionary. Peter Hudis, however, goes to pains to describe how Fanon was “alert to the dangers of political Islam”. This is such an interesting statement, given how we know that the Algerian Liberation Movement was so informative of Fanon’s political and philosophical views. Fanon could have moved to any country in Africa during this period of his life and been involved with the many liberation movements across the continent, and in fact the world. He chose to stay in Algeria, and writes about how the movement, rooted in many ways in Islam, changed his philosophy. His views on Nationalism also echo that of Islam. I personally find the term “Islamic Fundamentalism” rooted in oriental fear mongering of Islam. It’s not a phrase Fanon uses, and it’s unfortunate that Peter Hudis regresses to this language in his own exploration of Fanon’s political ideologies.

Something I found incredibly interesting about from this book, other than Fanon’s life, was the revelation of how evil France was (is?). I didn’t know that France built an electronic fence on the borders of Algeria and Tunisia and Algeria and Morocco to keep out arms and ammunition. I thought building walls was an American and Israeli tactic. It appears they learnt it from the French! Fanon, for his part was responsible for finding an alternative route, and spent much of the 1960’s mapping out the “southern front” of the Algerian revolution, which involved getting ammunition from West Africa to Southern Algeria.

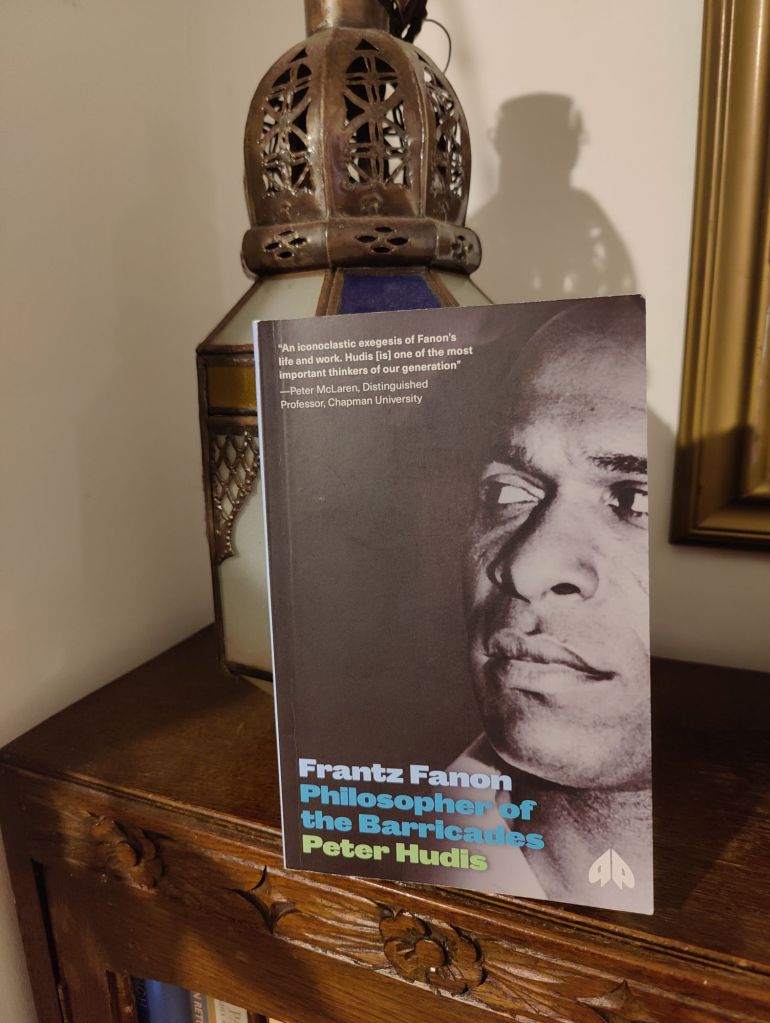

Fanon is a fascinating figure, and without doubt, Philosopher of the Barricades has made me want to read many of Fanons works, especially those he penned in later life. I had no idea he was linked to the Algerian revolution, another topic I’m keen to learn more about. Fanon’s evolution of thoughts and ideas is so clearly documented, and reading this critical biography made him come to life. His rejection of his earlier ideas, his frank attitude towards violence and revolution, and his ability to want to learn about the human experience makes him one of the very few philosophical thinkers in the West I’m actually interested in learning from. His work highlights the hypocrisy of Western society and how important it is to not confuse the experiences of white, colonial powers as that of all humans. His was a rare voice, who put his values and principles to practise, as a revolutionary. In a world that is struggling to learn the lessons from history, refusing to move away from capitalism and racism, (and other political structures imposed on us from our colonisers) learning about Frantz Fanon, Philosopher of the Barricades, might actually help us accept that who we are, and what we believe, is enough.

Yhus is such an interesting and thorough review, thank you for sharing it. Fanon was a remarkable person, I haven’t read his work, but I have been interested to know more.

LikeLike